Geo-Politics and Banking: Caught in the Middle

In January of 2019 I was invited to Iran to meet with the Central Bank Governor to discuss the future of banking, crypto and what opportunities Iran has once sanctions eventually are dropped.

I've been to Iran three times over the space of the last 20 years, my first and second visit was in 2006 and 2008 while I lived in Dubai. Each time has been a positive experience and I've found Tehran a wonderful city and the people friendly and inviting. I know that's not the picture we have of Iran in the West, but nonetheless it is the reality I've found.

Image 1: Bank 4.0 book signing in Tehran, Jan 2019 (Credit: Tosan)

In context, however, it needs to be said that I've also visited and met with Central Bank governors in dozens of geographies. I've met with the Peoples Bank of China, MAS, HKMA, FCA, FED, FDIC, OCC, CFPB, Norges Bank, Banco Central in Chile, Bank of Thailand, APRA, Bank Negara (Malaysia), and many more, but most memorably, I had the privilege to advise the Special Advisor to the President on Banking and the National Economic Council team at the White House. This week I'm in Zürich, Switzerland meeting with the Swiss National Bank and speaking at the Swiss Banking Association's annual event. As a bestselling author in the fintech space that writes frequently on policy, this is an essential part of my work.

Image 2 - Alex Sion and I outside the West Wing entrance in 2016 (Author's own)

In late 2019, however, HSBC suspended my accounts citing my business dealings with Iran pending an internal audit. Now keep in mind I have never transacted with an Iranian bank, I've never used my credit card in Iran (in fact US card schemes don't operate there due to sanctions), and I've never received money from an Iranian company or individual. Ultimately the audit cleared me of any issues and restored my account, but I had to agree in writing that I would not visit Iran or North Korea in the future, otherwise HSBC advised they could suspend my account permanently. The obvious question I had was, what triggered the audit in the first place, given my HSBC account was never used to transact with any business in Iran? And if I was pinged just for visiting Iran, imagine the size of the machinery working within banks to police this sort of activity. Who initiated the audit, was it a FATCA response because of my US residency in the past? I'm yet to find out.

Banks Fail at Financial Crime Policing

There's been a move over recent years, at least since the Patriot Act was put in place, to enlist banks in the prevention of anti-money laundering (AML), to track suspicious transactions, prevent terrorist financing, and to enforce sanctions. Financial crime compliance costs rose 33% in 2020 to $35.2 Billion in the United States alone. Some estimates put financial crime compliance costs as high as $10,000 per employee across the global banking space, or about 6-10% of income. Those costs are mostly wasted.

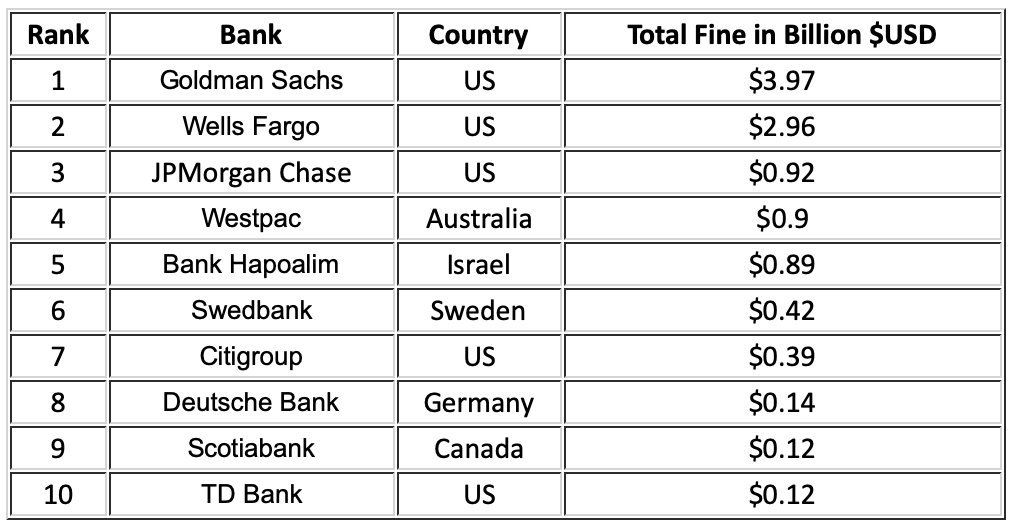

McKinsey research showed that despite this massive global activity, financial crime compliance is effective at eliminating less than 1% of global financial crime. So why do banks keep doing it, because the fines for failure to comply keep going up! In 2020, three US banks made up half of the $11.4Bn in fines for AML/KYC issues, fraud and non-compliance.

Source: Fintech Futures/FinBold

In 2018, the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) published Report to the Nations: 2018 Global Study on Occupational Fraud and Abuse. This study covered employee fraud across 24 industries, but the financial services sector had the highest rate of internal fraud of all of the industry sectors reviewed. In fact, the largest frauds in banking tend to be internal crimes rather than external. Additional research detailed the banks and brokers that have been hit with the biggest financial penalties and the most commonly fined offenses - with one bank racking up $82bn in fines.

It is not unreasonable, then, to conclude that current financial crime efforts are either simply not working, or that these efforts are designed more to give the appearance of enforcing policy, rather than actually preventing crime. If we really want to stop AML and fraud, it appears more serious industry reform is needed to prevent employee related fraud which is a far larger problem than FATCA, AML or terrorist financing breaches by individuals.

Banks Enforcing Policy or Politics?

In the closing days of the Trump administration, new sanctions were leveled against Iran. But the big case that illustrates the political nature of AML and fraud policing is, of course, the Supreme Court of British Columbia hearing an extradition case against Meng Wanzhou, CFO of Chinese Tech Giant Huawei.

Officials with the US justice department allege that in 2013, Meng misled bankers at HSBC about the relationship between Huawei and affiliate SkyCom, putting the bank at risk of breaching US sanctions against Iran. The US wants her extradited to New York to face criminal charges.

"Meng Wanzhou extradition case wraps up but verdict will take months", The Guardian, 18th August 2021

Here's the thing. HSBC has already confirmed that no fraud was committed, and that HSBC suffered no losses as a result of the Huawei and SkyCom deal that is at question. HSBC emails presented as evidence in the court, have been presented by Meng Wanzhou's defense team to show that senior officials within HSBC were long aware of SkyCom's business in Iran and that Huawei had been transparent about this issue. But that was before the Trump administration came into power, and subsequently blamed the "Wuhan Flu" on China, started a disastrous trade war, and used an executive order to go after Huawei specifically in relation to their 5G technology.

The extradition order for Meng Wanzhou was the result of US policy, not any specific fraud or crime committed according to current banking regulations. If no fraud was committed, then what is the basis for the extradition?

Caught in the Middle

Michael Spavor and a second Canadian, Michael Kovrig, were arrested by Chinese officials in December 2018, days after Canada arrested the Huawei executive on a US extradition request. This sort of diplomatic posturing and action is not unusual, but asking global bank brands to be the legal enforcement agency of any single government administration is fraught with complexities.

HSBC is really just caught in the middle of this geo-political spat. If my experience is common, imagine the amount of time and money that HSBC and banks like them incur just due to the administration's policy doctrine in Washington at that time.

I think we need to see some real global regulatory reform here in respect to true financial crime and money laundering issues. Banks should not need to take sides geo-politically when it comes to policy or sanctions beyond simply turning off the ability to conduct transactions with a politically sanctioned country or a criminal organization. Asking banks to police policy that might change on an administrative whim, at significant cost financially and reputationally, is only going to make banking more expensive for everyone.

It's also time we recognize that current terrorist financing and financial crime actions are woefully unsuccessful and that a new system is needed. The amount of false positives alone, are probably evidence for that, if not the huge compliance expenditure banks are saddled with. I know that the Patriot Act seemed like a good idea at the time, but it gave governments like the US broad powers related to tracking our financial activity that in retrospect is barely justifiable.

Ultimately I think the solution lies in global regulatory data sharing alliances and the use of Artificial Intelligence. But this will take a decade or two to wash out.

Trending

-

1 Building a Strong Financial Foundation: Saving, Investing, and Retirement Planning

Daniel Hall -

2 Franchise Investment Pitfalls to Avoid: A Beginner's Checklist

Daniel Hall -

3 Why Selling to an iBuyer Could Be the Best Move for Your Home

Daniel Hall -

4 Financial Tips for Businesses: Reducing Expenses Without Sacrificing Quality

Daniel Hall -

5 9 Tips to Help You Secure a Graduate Job in Finance

Daniel Hall

Comments