College Completion Rates

Children in the United States hear a huge amount about the importance of getting a college degree.

But most of them don’t.

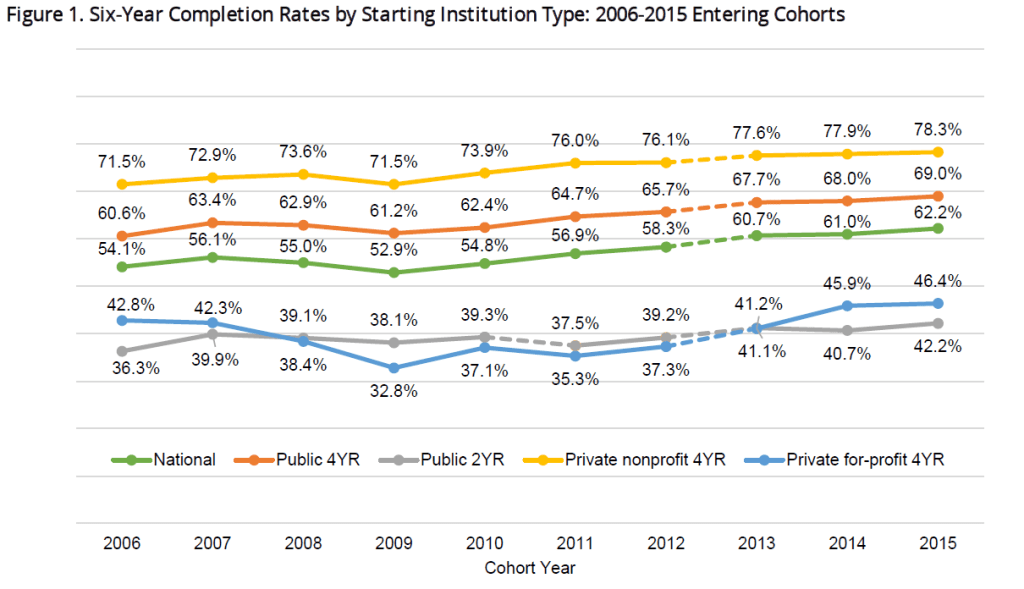

A standard measure of college graduation rates is to look at the “six-year” rate–that is, the share of people who complete a college degree within six years of starting it. Here’s a figure on six-year completion rates from Completing College: National and State Reports, published by the National Student Clearinghouse® Research Center (February 3, 2022).

Completion rates for getting any kind of college degree six years after starting have been creeping up over time. Overall, the green line shows the national rate is 62.2 percent for those who started college six years ago.

But of course, not all students start attending college in the first place. The right-leaning think-tank American Compass has published “A Guide to College-for-All” (January 2022) that offers some background information on the topic. The report looks at the pipeline from K-12 education to college and notes:

Put it all together, and the college pipeline proves incredibly leaky. Out of 100 high school students, 13 won’t complete high school, another 29 will complete high school but not enroll in college, and 27 will enroll in college but fail to complete a degree. Of the 31 who do earn a college degree, 13 will end up in jobs that don’t require one. That leaves just 18 of 100 young Americans—call them the Fortunate Fifth—actually moving smoothly from high school to college to career.

Many policymakers talk about the goal of college-for-all, but it doesn’t seem to me that they are actually serious. After all, it would require a massive upgrade of K-12 education so that everyone would graduate and be able to do college-level work. In addition, it would then require an enormous expansion of America’s colleges and universities so that they could handle the vastly increased enrollment of college-for-all. While our society does seek incremental improvements in education, here and there, there has not been substantial political support for this kind of radical change.

When most people say college-for-all, they actually in practice mean something like: “It’s good to keep your aspirations high, especially when you’re young, and we should reduce any financial barriers to higher education.” But when students in K-12 education get a heavy and repeated emphasis on college-for-all, it’s difficult for them not to also come to believe that college is “success” and lack of college is not. For students who were in the bottom third or so of academic standing throughout their K-12 experience, telling them that they need another four years of school to be a “success” is the opposite of encouraging.

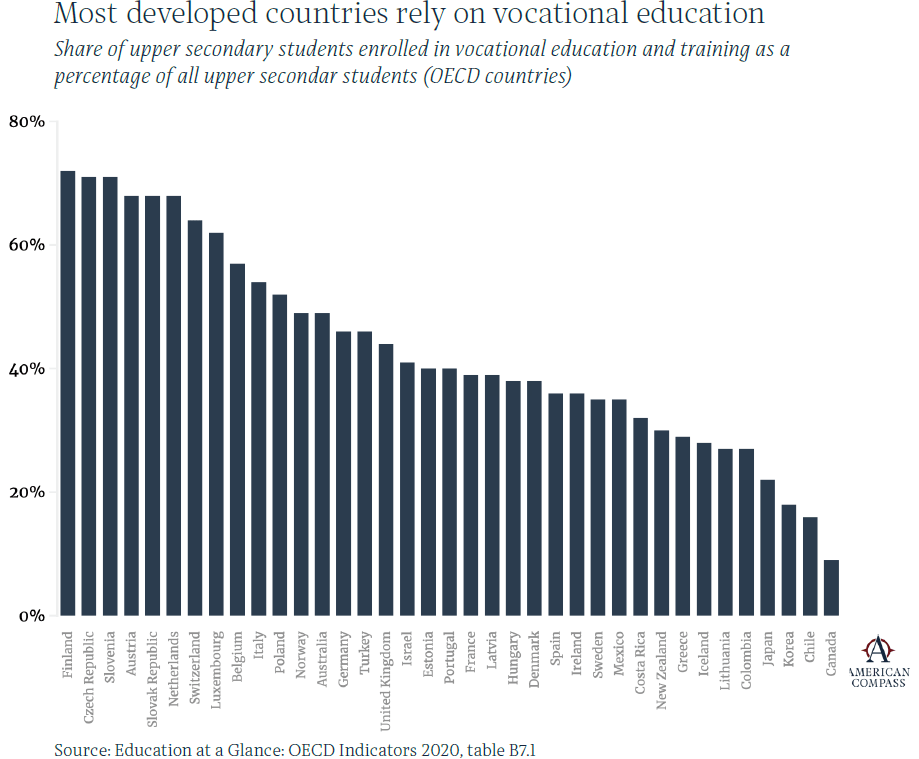

It seems to me that what many students want is a pathway to a career-type job, by which I mean a job with skills, which offers decent wages, reliable employment and the possibility of higher pay and responsibility over time. The American Compass report offers some interesting charts on how this might be achieved without making college-for-all the goal. Here’s one based on OECD data:

In most countries, something like 20-50% of high school students are in classes aimed at vocational education and training. However, if you search the figure above for the US level, you will not find it. As a note reports under the table:

The United States is the only country that the OECD excludes from its statistics on vocational education. It reports, “All countries except the United States have some students enrolled in vocational upper secondary education. In the United States, there is no distinct vocational path at upper secondary level, although optional vocational courses are offered within the general track and VET programmes start at the post-secondary level.”

When you are the one high-income country not even included in these statistics, because “there is no distinct vocational path at upper secondary level,” it seems time to reconsider. I’m open to a wide array of possibilities here, from vocational classes to apprenticeships to training programs run through community colleges. Such programs work best when there is a widespread national effort to connect students to real-world employers. However, the United States has largely chosen “to place all its eggs in the college attendance basket,” as the American Compass report puts it:

Our funding decisions also make it clear: We send hundreds of billions of dollars annually toward higher education while slowly starving non college pathways of support. This was an intentional choice and one that differs dramatically from the model embraced in most developed economies, where non college pathways enjoy equitable support.

Trending

-

1 UK Tech Sector Secures a Third of European VC Funding in 2024

Azamat Abdoullaev -

2 France’s Main Problem is Socialism, Not Elections

Daniel Lacalle -

3 Fed Chair Jerome Powell Reports 'Modest' Progress in Inflation Fight

Daniel Lacalle -

4 AI Investments Drive 47% Increase in US Venture Capital Funding

Felix Yim -

5 The Future of Work: How Significance Drives Employee Engagement

Daniel Burrus

Comments