From Multilateralism to Friend-Shoring

Offshoring is when production by US companies happens in other places.

Onshoring is when at least some of that production that had been done in foreign places shifts back inside US borders. Friend-shoring is when countries decide, as a matter of policy, that they will emphasize and focus on trade with friendly nations. The idea of friend-shoring is being discussed at high levels, as T. Clifton Morgan, Constantinos Syropoulos, and Yoto V. Yotov discuss in “Economic Sanctions: Evolution, Consequences, and Challenges” (Journal of Economic Perspectives, Winter 2023; full disclosure, I work as Managing Editor of JEP).

The main focus of their article is on the rising use of trade sanctions and how well they work (as discussed here). But given the rise in US protectionism that started during the Trump administration and has continued into the Biden presidency, the prospect of friend-shoring also comes up. They write:

Finally, as states seek to reduce their vulnerability to sanctions, what ramifications may arise for the international economic and political system? For example, when members of the World Trade Organization mix trade and security policies, as has been the case in the Russia-Ukraine crisis, the survival of WTO and the rules-based approach to policymaking may be at risk. Comments from prominent officials suggest that the United States and the European Union may already be moving away from global multilateralism toward cooperation with limited circles of friends.

In [US Secretary of the Treasury] Janet Yellen’s (2022) words: “[W]e need to modernize the multilateral approach we have used to build trade integration. Our objective should be to achieve free but secure trade. We cannot allow countries to use their market position in key raw materials, technologies, or products to have the power to disrupt our economy or exercise unwanted geopolitical leverage. So let’s build on and deepen economic integration . . . And let’s do it with the countries we know we can count on. Favoring the friend-shoring of supply chains to a large number of trusted countries . . . will lower the risks to our economy as well as to our trusted trade partners.”

In similar spirit, Christine Lagarde (2022), President of the European Central Bank, remarked: “Russia’s unprovoked aggression has triggered a fundamental reassessment of economic relations and dependencies in our globalised economy . . . Today, rising geopolitical tensions mean our global economy is changing . . . [O]ne can already see the emergence of three distinct shifts in global trade. These are the shifts from dependence to diversification, from efficiency to security, and from globalisation to regionalisation.

Given the disruptions of the pandemic, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and China’s military build-up, there are of course reasons for firms everywhere to shorten their supply chains, and practice some combination of reshoring and friend-shoring. But the current favorite flavor of trade policy in the US and Europe does more than that: It’s more about government subsidies for favored domestic industries, rather than about recalculating gains from trade. It looks as if policymakers may need to learn all over again that while some parts of an economy can subsidize other parts, the gains of the favored firms that get such subsidies don’t mean that the economy as a whole is actually better off. In addition, whatever the geopolitical reasons for reducing international trade, such reductions impose economic costs.

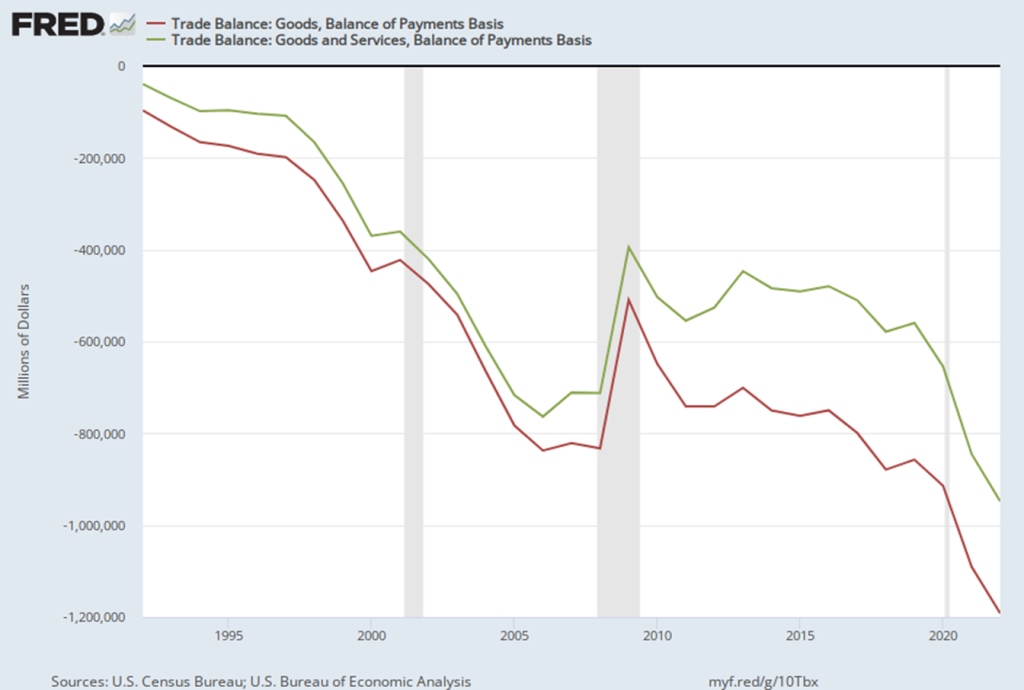

I won’t rehearse those arguments here. But remember when President Trump first imposed substantial trade sanctions on China? He tweeted in March 2018: ”When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win. Example, when we are down $100 billion with a certain country and they get cute, don’t trade anymore-we win big. It’s easy!” He imposed tariffs, and here’s the pattern of the US trade deficit since then (red line is trade deficit for goods only; green line is for goods and services combined. At this point, it’s pretty clear (as it has been many times before) that imposing tariffs is not the answer to reducing the US trade deficit, nor to jump-starting US productivity and competitiveness.

Less trade and more government subsidies to favored industries and firms is not a likely path to improved trade balances, or to prosperity in general.

Trending

-

1 UK Tech Sector Secures a Third of European VC Funding in 2024

Azamat Abdoullaev -

2 France’s Main Problem is Socialism, Not Elections

Daniel Lacalle -

3 Fed Chair Jerome Powell Reports 'Modest' Progress in Inflation Fight

Daniel Lacalle -

4 AI Investments Drive 47% Increase in US Venture Capital Funding

Felix Yim -

5 The Future of Work: How Significance Drives Employee Engagement

Daniel Burrus

Comments