Investing in Small Children

The idea that if society invests in small children, we will see a later social payoff, has a powerful intuitive and humanitarian pull.

But what about hard evidence? For example, can we trace a randomly distributed set of benefits given to small children and see evidence of payoffs for those children in later life, compared to the children who did not receive such benefits? The research challenges here are considerable, and a group of studies are beginning to meet them.

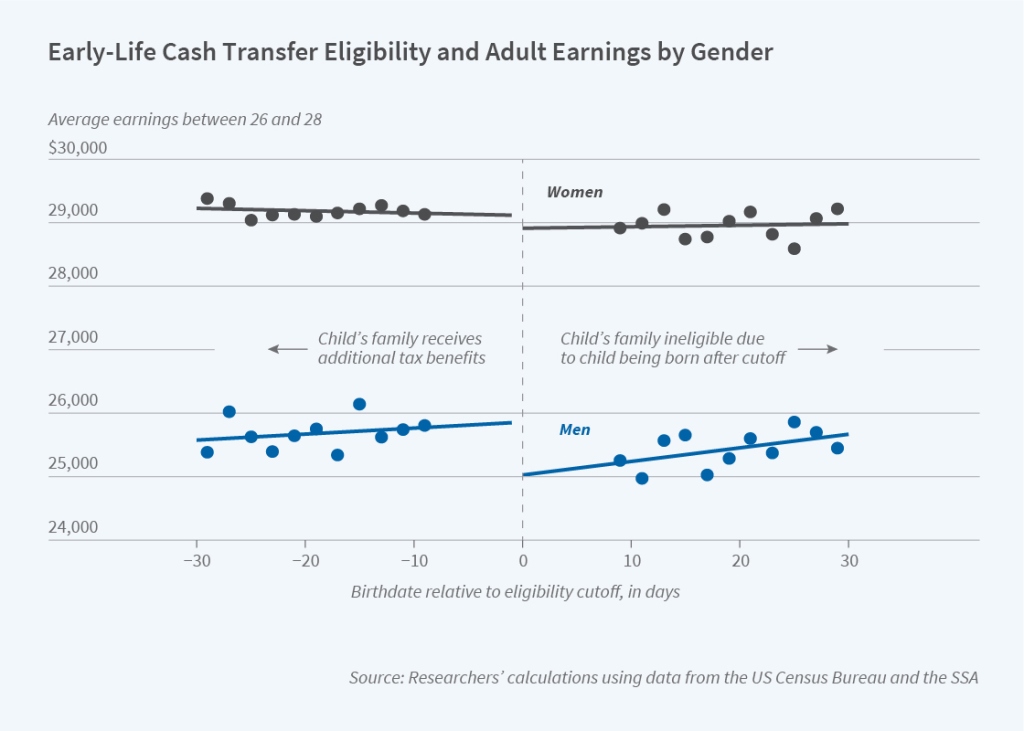

As a recent example, consider “Investing in Infants: The Lasting Effects of Cash Transfers to New Families,” by Andrew C. Barr, Jonathan Eggleston and Alexander A. Smith (NBER Working Paper 30373, August 2022). The authors look at tax data going back to 1979. In particular, they look at low-income families having first children in either December or January. The difference is that families with children born in December are eligible for an additional tax deduction and a higher earned income tax credit the following year. For these families, the additional benefits averaged about 10% of household income. If we make the plausible assumptions that the babies born in December are not fundamentally different from those born in January, and that the groups of families are otherwise similar (remember, they are eligible for the same programs), we then have what social scientists call a “natural experiment.” Do the children whose families got the extra income boost during their first year of life do better later in life?

The figure illustrates some of the results. Those children whose families received the additional tax benefit in their first year of life earned more as 26-28 year-olds.

The results over time can be summarized this way: “The additional earnings generate an increase in federal income tax revenues large enough, in present discounted value, to cover the cost of the higher tax credits for parents with newborns.”

Anna Aizer, Hilary Hoynes, and Adriana Lleras-Muney offer an overview of research in this area in “Children and the US Social Safety Net: Balancing Disincentives for Adults and Benefits for Children” (Journal of Economic Perspectives, Spring 2022). They emphasize that, in the past, studies of benefits for low-income families with children tended to focus on how the work incentives of adults might be affected, but often had little or nothing to say about possible long-run benefits from supporting the children in such families.

For example, when the food stamp program was first being enacted in the 1960s, it was not enacted everywhere at once, but instead was rolled out across different counties from 1961 to 1974 in an essentially random way. Thus, some low-income children were randomly born into counties where their families received food stamps, and others were not. Developments in the availability of long-run data make it possible to compare across these groups. Aizer et al. write: “They find that access to food stamps in early childhood leads to increases in completed education, earnings, neighborhood quality, and home ownership as well as reductions in poverty, mortality, and incarceration. In both these studies, the gains are large and increasing in length of exposure between conception and age five, after which there appear to be few effects, suggesting that early childhood may be a sensitive window for nutritional inputs.”

Indeed, an overview of 133 different policy interventions, looking at different age groups, found considerable variation in the effects (Nathaniel Hendren and Ben Sprung-Keyser. 2020. “A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (3): 1209–318). Not everything works well! But when looking at programs for children as a group, spending on child education, child health, and improved college access all ultimately paid for themselves in terms of higher future tax revenues–and this measure leaves out benefits like improved health and lower crime rates that do not directly manifest in the form of higher income earned and tax revenues paid.

Small children don’t have a high public profile. They don’t march in political demonstrations. They don’t vote. They lack power to shape their daily environment. Moreover, the parents of small children are often suffering from a lack of time and sleep, and it’s probably not the most flexible period of their life to devote energy to political activism. But what happens to young children has lasting life effects. As one current policy choice, the Child Tax Credit for low-income families was dramatically expanded during 2021, by enough that the share of children living in households below the poverty declined by one-third. The existing evidence from earlier studies strongly suggests that the additional costs of this program will be repaid in higher tax revenues over time. Greater equality of opportunity for young children pays off.

In addition, there has been a past tendency among economists to look at policies which have an effect on children primarily in terms of how those policies affect parents. For example, discussions of policies like welfare payments or food stamps often focused on how they might affect work or marriage incentives for parents–not on how they affected the long-run prospects of young children.

Trending

-

1 UK Tech Sector Secures a Third of European VC Funding in 2024

Azamat Abdoullaev -

2 France’s Main Problem is Socialism, Not Elections

Daniel Lacalle -

3 Fed Chair Jerome Powell Reports 'Modest' Progress in Inflation Fight

Daniel Lacalle -

4 AI Investments Drive 47% Increase in US Venture Capital Funding

Felix Yim -

5 The Future of Work: How Significance Drives Employee Engagement

Daniel Burrus

Comments