Behavioural economics, at its simplest, is incorporating psychology in the study of economics and economic decision-making. While Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman can easily be called the fathers of behavioural economics, Thaler's work has truly transformed behavioural economics into behavioural science.

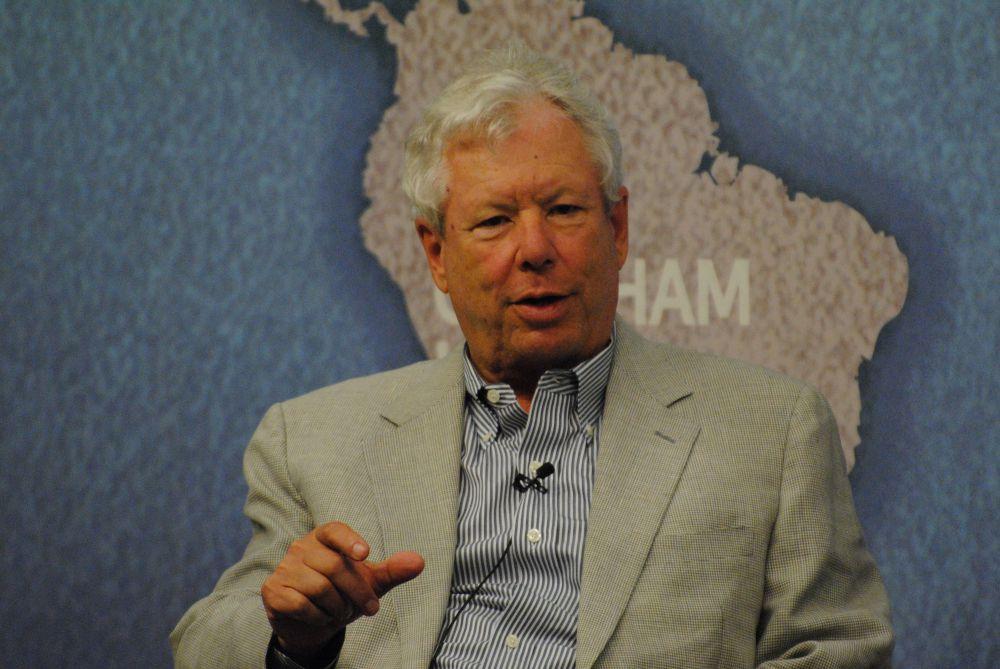

Richard Thaler, 72, is currently Professor of Economics and Director of the Center for Decision Research at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. He is a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), an American private nonprofit research organization. He is also on the Academic Advisory Panel of the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), a social purpose company jointly owned by the UK Government.

Thaler's first behavioural paper 'Toward a Positive Theory of Consumer Choice' (1980) was rejected by multiple journals, his doctoral dissertation 'The Value of Saving A Life: A Market Estimate' (1974) was unimpressive even to his supervisor, and many years later his appointment to University of Chicago was shrugged off as mistakes of a generation by the Nobel laureates associated with the university at that time.

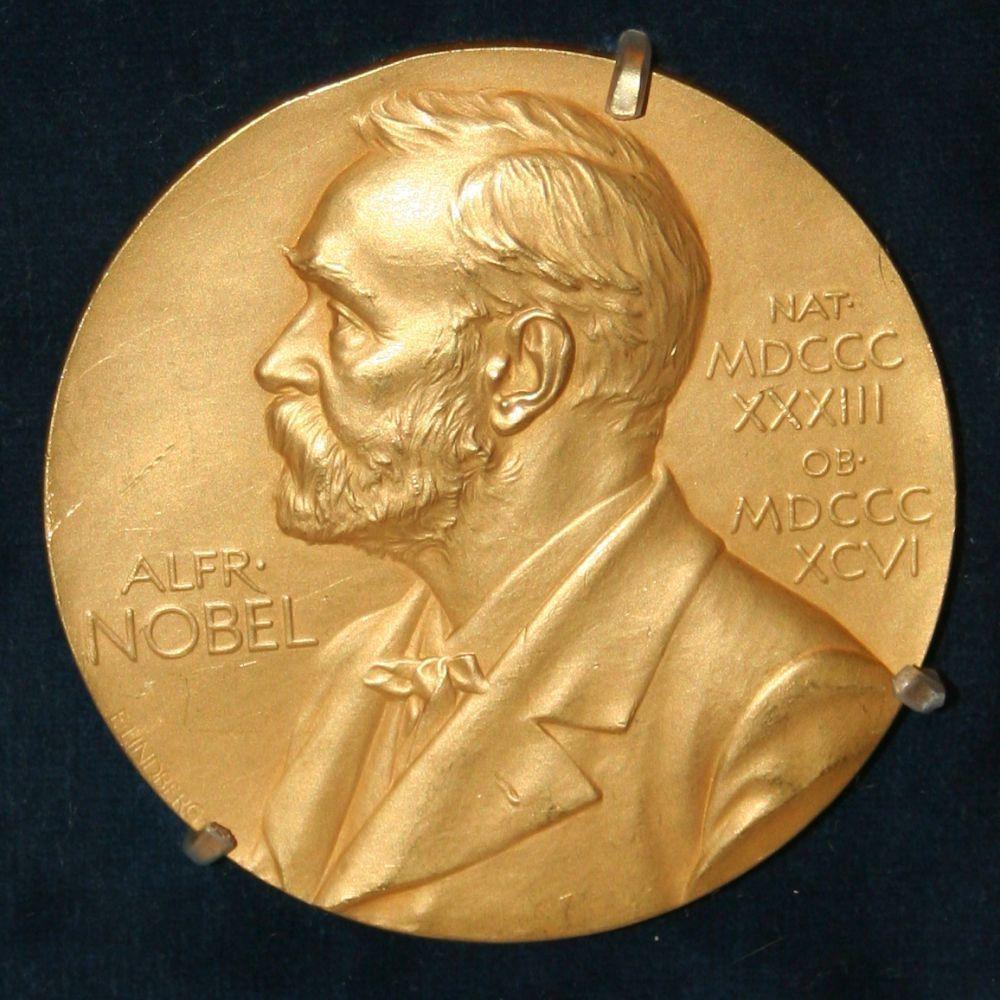

The Nobel Prize committee has recognised his work on three areas: limited rationality, social preferences, and lack of self-control. His proposals and experiments have been termed as ground-breaking. Richard's work such as his Model of Mental Accounting has transformed the way Americans save money and his experiments on Judgements of Fairness (along with Daniel Kahneman) show systematic deviations in the assumed human behaviour as selfish or rational. Behavioural finance too has seen revolution, where Thaler along with his other colleagues has shown investors have a tendency to stick with their poor assets and how they can change this, through the concepts of Endowment Effect & Loss Aversion.

Chicago Booth's announcement of Thaler's award is the most accurate and easily understood:

He investigates the implications of relaxing the standard economic assumption that everyone in the economy is rational and selfish, instead entertaining the possibility that some of the agents in the economy are sometimes human.

Behavioural Economics (& Science) which struggles even today to find credibility amongst some intellectual circles and is disbelieved as a subject of 'obvious common-sense' to the general public, was a social science much ahead of its time in the early 70s when Kahneman, Tversky and Thaler nursed and ruled it.

With Richard Thaler's Nobel comes a lot of noise (in the form of celebration of his work and of the science): a great deal written by the scholars of BE and the value that it has created has resurfaced, which is likely to generate momentum for this underdog, get it the front seat in the policy circles of more countries and motivate more economists to opt for this economics of experiment based policy making.

Thaler will receive 9 million Swedish kronor as prize money and he says that he will "try to spend it as irrationally as possible."

Comments