Some Economics of Tobacco Regulation

Cigarette smoking in the United States is implicated in about 480,000 deaths each year–about one in five deaths.

Cigarette smokers on average lose about 10 years of life expectancy. According to a US Surgeon General report in 2020:

Tobacco use remains the number one cause of preventable disease, disability, and death in the United States. Approximately 34 million American adults currently smoke cigarettes, with most of them smoking daily. Nearly all adult smokers have been smoking since adolescence. More than two-thirds of smokers say they want to quit, and every day thousands try to quit. But because the nicotine in cigarettes is highly addictive, it takes most smokers multiple attempts to quit for good.

Philip DeCicca, Donald Kenkel, and Michael F. Lovenheim summarize the evidence on “The Economics of Tobacco Regulation: A Comprehensive Review” (Journal of Economic Literature, September 2022, 883-970). Of course, I can’t hope to do justice to their work in a blog post, but here are some of the points that caught my eye.

1. US efforts at smoking regulation changed dramatically in the late 1990s, with an enormous jump in cigarette taxes and smoking restrictions.

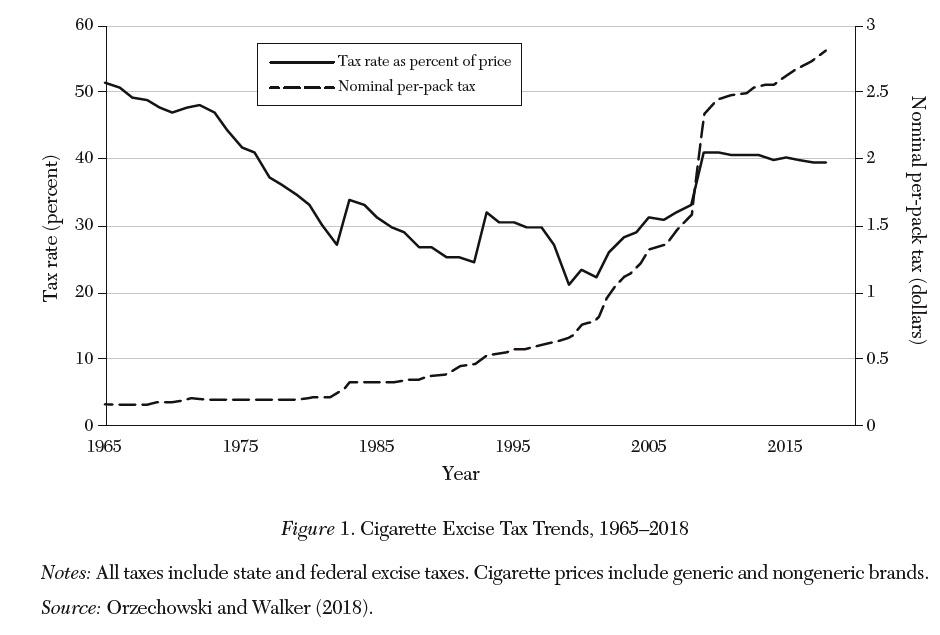

For example, here’s a figure showing the combined federal and state tax rate on cigarettes as a percent of the price (solid line) and as price-per-pack (dashed line). In both cases, a sharp rise is apparent from roughly 1996 up through 2008.

In addition, smoking bans have risen substantially.

Governments around the world have implemented smoking bans sporadically over the past five decades, but they have become much more prevalent over the past two decades. … [W]orkplace, bar, and restaurant smoke- free indoor air laws became increasingly common. As of 2000, no state had yet passed a comprehensive ban on smoking in these areas, although some states had more targeted bans. From 2000–2009, the fraction of the US population covered by smoke- free worksite laws increased from 3 percent to 54 percent, and the fraction covered by smoke- free restaurant laws increased from 13 percent to 63 percent … Since the turn of the century, the increased taxation and regulation of cigarettes and tobacco is unprecedented and dramatic.

2. Given that tobacco usage is being discouraged in a number of different ways, all at the same time, it’s difficult for researchers to sort out the individual effects of, say, cigarette taxes vs. workplace smoking bans vs. government-mandated health warnings vs. changing levels of social approval.

3. My previous understanding of the conventional wisdom was that demand for cigarettes from adult smokers was relatively inelastic, while demand from younger smokers was relatively elastic. The underlying belief was that (as a group) adult smokers have had a more long-lasting tobacco habit and have more income, so it was harder for them to shake their tobacco habit, while the tobacco usage of younger smokers is more malleable. This conventional wisdom may need some adjustments.

The consensus from the last comprehensive review of the research that was conducted 20 years ago (Chaloupka and Warner 2000) indicates that adult cigarette demand is inelastic. More recent research from a time period of much higher cigarette taxes and lower smoking rates supports this consensus, however, there is also evidence that traditional methods of estimating cigarette price responsiveness overstate price elasticities of demand. As well, more recent research casts doubt on the prior consensus that youth smoking demand is more price-elastic than adult demand; the most credible studies on youth smoking indicate little relationship between smoking initiation and cigarette taxes. The inelastic nature of cigarette demand suggests cigarette excise taxes are an efficient revenue-generating instrument.

To put it another way, higher cigarette taxes do a decent job of collecting revenue, but they don’t do much to discourage smoking.

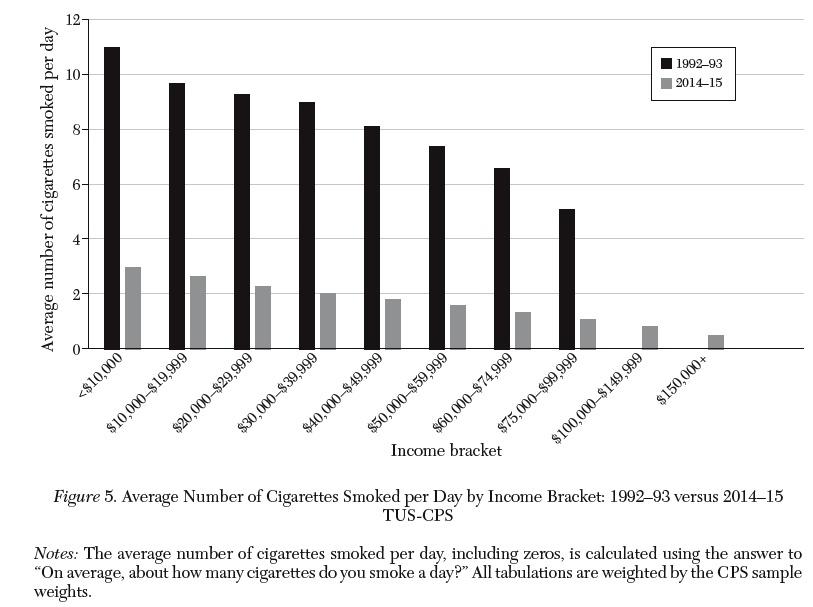

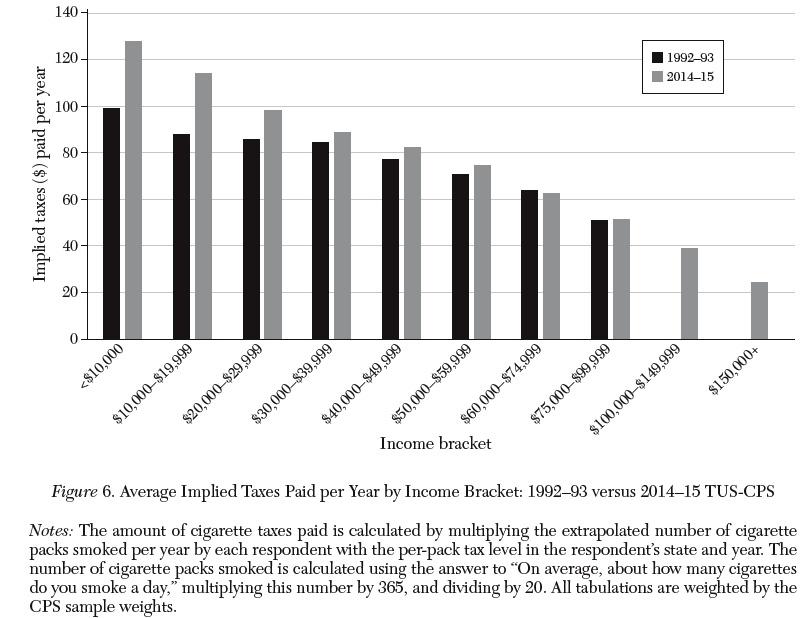

4) If cigarette taxes are really about revenue collection, because they don’t do much to discourage smoking, then it becomes especially relevant that low-income people tend to smoke more, and thus end up paying more in cigarette taxes. This figure shows cigarette use by income group; the next figure shows cigarette taxes paid by income group.

5) Broadly speaking, there are two economic justifications for cigarette taxes. One is what economists call “externalities,” which are the costs the cigarette smokers impose on others in ways including secondhand smoke and higher health care costs that are shared across public and private health insurance plans with non-smokers. The other is “internalities,” which are the costs that smokers who would like to quit, but find themselves trapped by nicotine addition, impose on themselves. The authors write:

However, evidence on the magnitude of the externalities created by smoking does not necessarily support current tax levels. Behavioral welfare economics research suggests that the internalities of smoking provide a potentially stronger rationale for higher taxes and stronger regulations. But the empirical evidence on the magnitudes of the internalities from smoking is surprisingly thin.

6) Finally, in reading the article, I find myself wondering if the US is, to some extent, substituting marijuana for tobacco cigarettes. As the authors point out, the few detailed research studies on this subject have not found such a link. However, in a big picture sense, the trendline for cigarette use is decidedly down over time, while the trendline for marijuana use is up. A recent Gallup poll reports that “[m}ore people in the U.S. are now smoking marijuana than cigarettes.” Evidence from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health doesn’t more-or-less backs up that claim:

Among people aged 12 or older in 2020, 20.7 percent (or 57.3 million people) used tobacco products or used an e-cigarette or other vaping device to vape nicotine in the past month. … In 2020, marijuana was the most commonly used illicit drug, with 17.9 percent of people aged 12 or older (or 49.6 million people) using it in the past year. The percentage was highest among young adults aged 18 to 25 (34.5 percent or 11.6 million people), followed by adults aged 26 or older (16.3 percent or 35.5 million people), then by adolescents aged 12 to 17 (10.1 percent or 2.5 million people).

However, about one-fifth of the tobacco product users didn’t smoke cigarettes, and with that adjustment, cigarette smoking would be a little below total marijuana use.

Trending

-

1 UK Tech Sector Secures a Third of European VC Funding in 2024

Azamat Abdoullaev -

2 France’s Main Problem is Socialism, Not Elections

Daniel Lacalle -

3 Fed Chair Jerome Powell Reports 'Modest' Progress in Inflation Fight

Daniel Lacalle -

4 AI Investments Drive 47% Increase in US Venture Capital Funding

Felix Yim -

5 The Future of Work: How Significance Drives Employee Engagement

Daniel Burrus

Comments