What is a Good Job in 2020? Here's What the Evidence Says

On the surface, it's easy to sketch what a "good job" means: having a job in the first place, along with good pay and access to benefits like health insurance.

But that quick description is far from adequate, for several interrelated reasons. When most of us think about a "good job," we have more than the paycheck in mind. Jobs can vary a lot in working conditions and predictability of hours. Jobs also vary according to whether the job offers a chance to develop useful skills and a chance for a career path over time. In turn, the extent to which a worker develops skills at a given job will affect whether that worker worker is a replaceable cog who can expect only minimal pay increases over time, or whether the worker will be in a position to get pay raises--or have options to be a leading candidate for jobs with other employers.

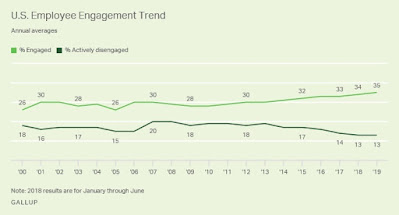

A majority of Americans do not consider themselves to be "engaged" with their jobs. According to Gallup polling, the share of US workers who viewed themselves as "engaged" in their jobs had risen to 35% in 2019, while 52% were "not engaged" and 13% were "actively disengaged." One suspects this level of engagement will drop after the pandemic recession.

What makes a "good job" or an engaging job? The classic research on this seems to come from the Job Characteristics Theory put forward by Greg R. Oldham and J. Richard Hackman back in a series of papers written in the the 1970s: for an overview, a useful starting point is their 1980 book Work Redesign. Here, I'll focus on their 2010 article in the Journal of Organizational Behavior summarizing some findings from this line of research over time, "Not what it was and not what it will be: The future of job design research" (31: pp. 463–479).

Oldham and Hackman point out that from the time when Adam Smith described making pins and back in the eighteenth century up through when Frederick W. Taylor led a wave of industrial engineers doing time-and-motions studies of workplace activities in the early 20th century, and up through the assembly line as viewed by companies like General Motors and Ford, the concept of job design focused on the division of labor. In my own view, the job design efforts of this period tended to view workers as robots that carried out a specified set of physical tasks, and the problem was how to make those worker-robots more effective.

Whatever the merits of this view for its place and time, it has clearly become outdated in the last half-century or so. Even in assembly-line work, companies like Toyota that cross-trained workers for a variety of different jobs, including on-the-spot quality control, developed much higher productivity than their US counterparts. And for the swelling numbers of service-related and information-related jobs, the idea of an extreme division of labor, micro-managed at every stage, often seemed somewhere between irrelevant and counterproductive. When worker motivation matters, the question of how to design a "good job" has a different focus.

By the 1960s, Frederick Herzberg is arguing that jobs often need to be enriched, rather than simplified. In the 1970s, Oldham and Hackman develop their Job Characteristics Theory, which they describe in the 2010 article like this:

We eventually settled on five ‘‘core’’ job characteristics: Skill variety (i.e., the degree to which the job requires a variety of different activities in carrying out the work, involving the use of a number of different skills and talents of the person), task identity (i.e., the degree to which the job requires doing a whole and identifiable piece of work from beginning to end), task significance (i.e., the degree to which the job has a substantial impact on the lives of other people, whether those people are in the immediate organization or the world at large), autonomy (i.e., the degree to which the job provides substantial freedom, independence, and discretion to the individual in scheduling the work and in determining the procedures to be used in carrying it out), and job-based feedback (i.e., the degree to which carrying out the work activities required by the job provides the individual with direct and clear information about the effectiveness of his or her performance).

When you start thinking about "good jobs" in these broader terms, the challenge of creating good jobs for a 21st century economy becomes more complex. A good job has what economists have called an element of "gift exchange," which means that a motivated worker stands ready to offer some extra effort and energy beyond the bare minimum, while a motivated employer stands ready to offer their workers at all skill levels some extra pay, training, and support beyond the bare minimum. A good job has a degree of stability and predictability in the present, along with prospects for growth of skills and corresponding pay raises in the future. We want good jobs to be available at all skill levels, so that there is a pathway in the job market for those with little experience or skill to work their way up. But in the current economy, the average time spent at a given job is declining and on-the-job training is in decline.

I certainly don't expect that we will ever reach a future in which jobs will be all about deep internal fulfillment, with a few giggles and some comradeship tossed in. As my wife and I remind each other when one of us has an especially tough day at the office, there's a reason they call it "work," which is closely related to the reason that you get paid for doing it.

But along with a concern for how quickly jobs will return in the aftermath of the pandemic recession, a primary long-term issue in the workforce is how to encourage the economy to develop more good jobs. I don't have a well-designed agenda to offer here. But what's needed goes well beyond our standard public arguments about whether firms should be required to offer certain minimum levels of wages and benefits.

Trending

-

1 UK Tech Sector Secures a Third of European VC Funding in 2024

Azamat Abdoullaev -

2 France’s Main Problem is Socialism, Not Elections

Daniel Lacalle -

3 Fed Chair Jerome Powell Reports 'Modest' Progress in Inflation Fight

Daniel Lacalle -

4 AI Investments Drive 47% Increase in US Venture Capital Funding

Felix Yim -

5 The Future of Work: How Significance Drives Employee Engagement

Daniel Burrus

Comments