The Rise of Telemedicine

Back in 2015, the American College of Physicians officially endorsed telemedicine — that is, providing health care services to a patient who is not in the same location as the provider.

Nonetheless, many health care providers continued to rely on in-person visits for nearly all of their patients, with occasional telephone follow-ups. When the pandemic hit, it induced the birth of telemedicine as a widespread practice, creating more potential job opportunities.

When I’ve chatted with doctors and other health care providers about the change, I’ve heard mainly two reactions: 1) a degree of surprise that telemedicine was working well for patients; and 2) a comment along the lines that “we were always willing to do it, but what changed is that insurance was willing to reimburse for it.” It’s of course not surprising that insurance reimbursement rules will drive the manner and type of health care that’s provided, but it’s always worth remembering.

Evidence on telemedicine is now becoming available. Kathleen Fear, Carly Hochreiter, abd Michael J. Hasselberg describe some results from the University of Rochester Medical Center in “Busting Three Myths About the Impact of Telemedicine Parity” (NEJM Catalyst, October 2022, vol. 3, #10, need a subscription or library to access). The U-Rochester med center is good sized: six full-service hospitals and nine urgent care centers, along with various specialty care hospitals and a network of primary care providers. Before the pandemic they were serving about two million outpatient visits per year.

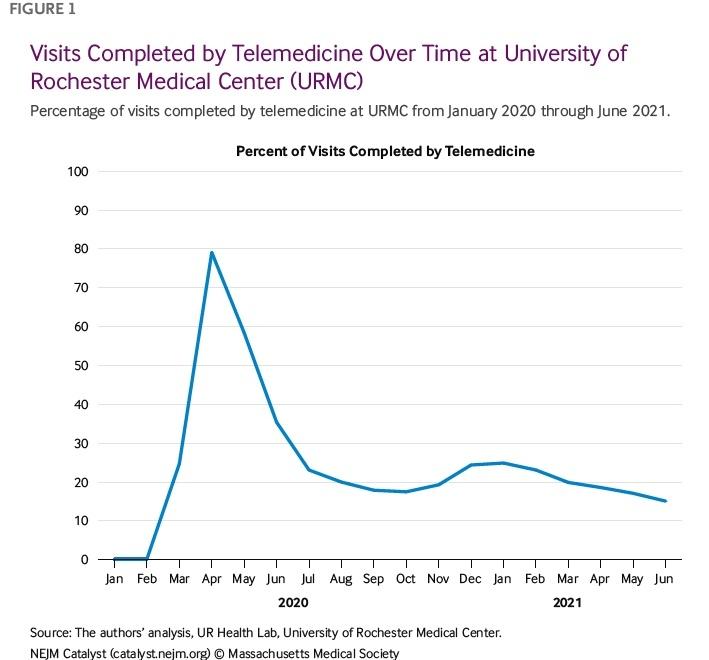

During the pandemic, telemedicine at U-Rochester spiked from essentially nothing to 80% of patient contacts, and now seems to have settled back to about 20%.

Here is how the authors summarize the experience:

Three beliefs — that telemedicine will reduce access for the most vulnerable patients; that reimbursement parity will encourage overuse of telemedicine; and that telemedicine is an ineffective way to care for patients — have for years formed the backbone of opposition to the widespread adoption of telemedicine. However, during the Covid-19 pandemic, institutions quickly pivoted to telemedicine at scale. Given this rapid move, the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) had a natural opportunity to test the assumptions that have shaped prior discussions. Using data collected from this large academic medical center, UR Health Lab explored whether vulnerable patients were less likely to access care via telemedicine than other patients; whether providers increased virtual visit volumes at the expense of in-person visits; and whether the care provided via telemedicine was lower quality or had unintended negative costs or consequences for patients. The analysis showed that there is no support for these three common notions about telemedicine.

At URMC, the most vulnerable patients had the highest uptake of telemedicine; not only did they complete a disproportionate share of telemedicine visits, but they also did so with lower no-show and cancellation rates. It is clear that at URMC, telemedicine makes medical care more accessible to patients who previously have experienced substantial barriers to care. Importantly, this access does not come at the expense of effectiveness. Providers do not order excessive amounts of additional testing to make up for the limitations of virtual visits. Patients do not end up in the ER or the hospital because their needs are not met during a telemedicine visit, and they also do not end up requiring additional in-person follow-up visits to supplement their telemedicine visit. As the pandemic continues to slow down, payers may start to resist long-term telemedicine coverage based on previous assumptions. However, the experience at URMC shows that telemedicine is a critical tool for closing care gaps for the most vulnerable patient populations without lowering the quality of care delivered or increasing short-term or long-term costs.

The authors are careful to point out that a substantial part of health care does need to be delivered in person–a point with which it would be hard to disagree. But this evidence also strongly suggests that telemedicine was dramatically underused before the pandemic. It raises broader questions as to whether there are other ways that the provision of health care is stuck in its ways, unwilling or unable to adopt promising innovations in a timely manner.

Trending

-

1 Mental Health Absences Cost NHS £2 Billion Yearly

Riddhi Doshi -

2 Gut Check: A Short Guide to Digestive Health

Daniel Hall -

3 London's EuroEyes Clinic Recognised as Leader in Cataract Correction

Mihir Gadhvi -

4 4 Innovations in Lab Sample Management Enhancing Research Precision

Emily Newton -

5 The Science Behind Addiction and How Rehabs Can Help

Daniel Hall

Comments