Soul Food for the Jewish Doctor

She was going to die, that was evident.

She collapsed in the bathroom at her home and they had started CPR there. The medics had done all the things you do when the heart stops—chest compressions, intubation, multiple doses of epinephrine, and the like. But the transport time from the house to our ER was beyond the time of survivability, and she was simply just too sick while she was alive to have any real hope of surviving now. A bit large, in the middle of her seventies, lots of scars and medications from visits past—these things just did not work in the favor of a few more years.

Typically, the medics would have run the entire arrest like this at the house, eventually pronouncing the victim there, saving us all the work and time and resources that go into trying to restart a soul that crossed over somewhere on the road a mile or two outside our doors, near the Speedway and Mattress Factory perhaps.

I suspect the word “family” in the midst of the patient report tipped me off. It was how the medic said “family.” It that had that ring of “they wouldn't have done well if we had called it there” tone to it that made me push the envelope a bit longer—a few more epi’s, some bicarb, more CPR, a bedside ultrasound, more tools out of the ACLS toolbox that I had opened a thousand cardiac arrests before.

But sometimes God has different plans, and tonight she was going home with Him . . . not with us.

So all that was left was for me to tell the family . . .

I had perhaps a preconceived notion how this was gonna go. I’d seen it countless times before: older African American woman who most likely stood tall as the matriarch of a large family who were infinitely emotionally and spiritually invested in what they envisioned would be a life that would never end. The “mama,” the “auntie,” the glue that rocked and sang and hugged and baked and fried and was the guardian of the Bible and the history and all the struggles hidden within. The faithful voice that was always there on the end of the phone, the warm presence filling that one special, worn chair in the first room off the front door.

They would scream, and fall to the ground, and tear at their clothes and streams of spittle and tears would fly through the air . . . yeah, I knew it was coming and I was gonna be the spark that lit that fire—the stranger-voice that would utter those words: “I’m so sorry, she has died.”

But instead they just stood there for a second—silent . . . the two of them. Staring at me and the young African American female minister who served as my chaperone.

I caught my reflection in the door behind her—an older white Jew, beaten down and tired by the world around me . . . and for a moment I felt the villain perhaps, like I was apologizing not only for breaking the news but . . . for being me, for being here. A part of me just wanted to get up out of the chair and move as quickly as I could to the safe confines of the trauma unit to seek refuge in the familiar.

But I didn’t move a muscle. I sat in the silence of the moment . . . and that’s when it began.

“I figured, doctor, thank you for trying . . . let me have a minute.” And the daughter took deep breath after deep breath. Her cousin held her own hand to her mouth while staring at the floor. The daughter shook her head “no” for a bit and then—like the gears had flipped—started nodding repetitively. And for the next five to ten solid minutes, I bore witness to grief wrapped in the loving arms of Jesus—hands to the heavens praising God for giving her this mother and the years of glory and wonder and strength. Shouts proclaiming the glory of God and Christ and Jesus and “thank You Almighty and she is soaring on angel wings . . . and I will be strong for her and I will honor her and I will carry on and I will live a life trusting in You, oh Lord, and that You know best and You will carry me through.” And the minister swayed like she knew the dance and chimed in with soft acknowledgments of “uhhh hmmm” and “praise Jesus,” and “Thy will be dones,” and all the proclamations that I imagine have been shouted from the pulpits and countless African American testimonials in country churches for generations far away from prying eyes.

And I couldn’t breathe.

There was a transcendent beauty to it all that lifted me up like I myself was being cradled by unseeing arms and I felt reborn in my own skin, like air had wafted into my own soul and awoken me from a deep sleep.

And as suddenly as it began it ended.

She took my hand. “Can I see her?”

“Absolutely.” I looked at her, deep in her eyes, and paused for the words . . . “First though, I want to thank you. I am Jewish, I struggle at times, especially now . . . that—” I choked up a bit . . . “That was one of the most beautiful things I have ever seen, or witnessed . . . how blessed your mom must have been to have you as a child. You have reaffirmed my own faith in God . . . your mother has reaffirmed my faith, and I want to thank you . . . both of you.”

And the minister said “hallelujah”—her eyes closed and palms to the sky.

And the daughter wrapped her arms around me and pulled me close like we had known each other all our lives and cried on my shoulder.

And I felt like I belonged.

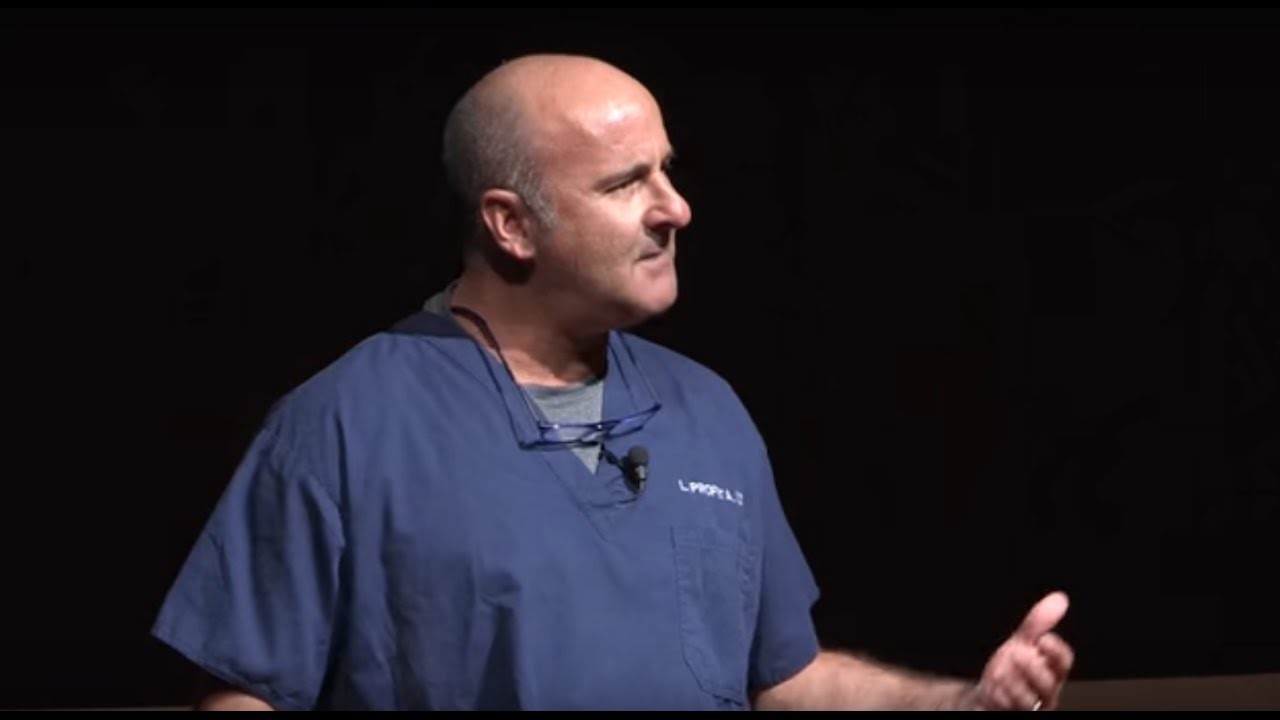

Dr. Louis M. Profeta is an emergency physician practicing in Indianapolis and a member of the Indianapolis Forensic Services Board. He is a national award-winning writer, public speaker and one of LinkedIn's Top Voices and the author of the critically acclaimed book, The Patient in Room Nine Says He's God. For other publications and for speaking dates, go to louisprofeta.com. For college speaking inquiries, contact bookings@greekuniversity.org.

Trending

-

1 Mental Health Absences Cost NHS £2 Billion Yearly

Riddhi Doshi -

2 Gut Check: A Short Guide to Digestive Health

Daniel Hall -

3 London's EuroEyes Clinic Recognised as Leader in Cataract Correction

Mihir Gadhvi -

4 4 Innovations in Lab Sample Management Enhancing Research Precision

Emily Newton -

5 The Science Behind Addiction and How Rehabs Can Help

Daniel Hall

Comments